Oppsummering av matverksted 12/2019

Siste matverksted i desember var annonsert å handle om sjokolademousse. Joda, vi hadde en systematisk smaking der vi skulle gi tilbakemelding på smaksopplevelsen av to porsjoner sjokolademousse. Saken var bare at det var nøyaktig samme sjokolademousse i begge porsjonene; eneste forskjell på de to var at de var servert fra skåler med ulik fasong.Lureri? Både ja og nei, men som arrangør følte jeg nok litt på dårlig samvittighet når jeg inviterte til matverksted med tema sjokolademousse, men der det egentlige formålet var å undersøke et annet aspekt enn selve moussen. Nemlig effekten av visuelle stimuli, i dette tilfellet former, på smaksopplevelse. Som kompensasjon for "Lureriet" brukte vi siste del av sesjonen til å lage og smake på en variant av sjokolademousse basert på kun sjokolade og vann, nemlig Hervé This sin sjokolade-chantilly som jeg har skrevet en del om tidligere (inkludert oppskrifter): Chocolate chantilly del 1 (hvit sjokolade), del 2 (melkesjokolade) og del 3 (mørk sjokolade).

Hvorfor servere samme dessert fra to ulike skåler?

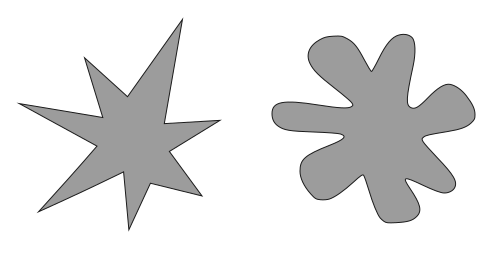

Anu Hopia og Tatu Lehtovaara, som gjennomfører sine parallelle "søster-matverksteder" i Helsingfors, tok initiativ til dette temaet etter inspirasjon fra en forskningsartikkel av Harrar og Spence (2013) i tidsskriftet Flavour: "The taste of cutlery: how the taste of food is affected by the weight, size, shape, and colour of the cutlery used to eat it". Charles Spence har sammen med andre i sin forskergruppe i Oxford forsket mye på temaet kryssmodale koblinger (crossmodal correspondences), assosiasjoner vi gjør på tvers av sanser: Vi assosierer ofte rød farge med søt smak, i hvert fall i større grad enn gult eller grønt, lyse dissonerende toner knyttes av mange til sur smak, og en klassisk studie der respondentene ble bedt om å knytte henholdsvis ordene "kiki" og "bouba" til de to fasongene nedenfor: |

| Hvilken er "kiki" og hvilken er "bouba"? Les mer om det her. (Ill.: Ronhjones @ wikimedia commons) |

Forsøket

Våre finske venner valgte å undersøke effekten av bestikket, der de deltakerne spiste sjokolademousse med hhv. vanlig stålskje med glatt overflate og gullfarget skje med mer ru overflate. Siden Klippfiskakademiet, som var vertskap også denne gangen, har dessertskåler av samme størrelse men ulik fasong valgte vi å knytte forsøket vårt til skålens fasong og la skjeene være like.Deltakerne fikk minimalt med informasjon ved ankomst, og vi var nøye med ordbruken for å forsøke å unngå å lede prøvesmakerne i en bestemt retning. Deltakerne ble delt i 5 + 6 der hver gruppe fikk smake mousse fra enten rund eller firkantet skål. Oppdraget deres var å streke under typiske karakteristiske assosiasjoner, smaker, usmaker og konsistenser som er relevante for sjokolade og mousse (se f.eks. her og her). Vi hentet inspirasjon fra en sensorisk metode som omtales som "check all that apply", CATA-metodikken og laget et skjema der deltakerne skulle streke under ord de syntes passet til smaksopplevelsen:

Ville deltakerne for eksempel oppleve moussen servert fra firkantede skåler som bitrere? I så fall kunne man tenke seg at flere som smakte fra firkentet skål streket under dette ordet enn de som smakte fra rund skål. Deltakerne ble så invitert til å bytte plass, uten at noe annet ble sagt, og smake nøyaktig samme mousse fra skål med annen fasong.

Resultatet

Et betydelig problem med undersøkelsen vår var det lave antallet respondenter: fem for den ene og 6 for den andre fasongen. De fikk anledning til å smake begge skåler, så i sum kan man si at vi hadde 11 resultater for hver av formene. Men vil regner andre runde som mindre gyldige resultater av (minst) to grunner:- deltakerne var allerede delvis mett etter første runde (ikke helt sant, da flere forsynte seg med en tredje porsjon etterpå; en stor kreditt til Klippfiskakademiets oppskrift og håndverk i å lage sjokolademousse)

- deltakerne kunne ha gjettet, eller begynt å tenke, at det her var noe rart, lagt merke til formen på skålene eller annet; "begynt å tenke" framfor å respondere intuitivt

Resultatene denne gangen ble dessverre ikke særlig klare med hensyn til de ulike beskrivende ordene; det tegnet seg ikke noe bestemt mønster. Var vi for få respondenter og at det hadde blitt et tydeligere resultat om vi var flere? Kunne ordene som deltakerne skulle streke under vært bedre valgt? I samtalen i etterkant ga tre personer likevel tilbakemelding om at de fikk assosiasjoner til karamell først når de smakte fra den runde skåla, fem deltakere mente at den runde skåla ga en sterkere assosiasjon til kaffe, en rapporterte at mousse fra den firkantede skåla opplevdes mer kornete. Så kanskje fasongen likevel hadde innvirkning?

|

| Et interessant bonus-resultat. Fatet startet med seks skåler av hver, slik endte det etter at deltakerne fikk forsyne seg fritt av restene. |

Ett artig resultat kom som en tilfeldighet.