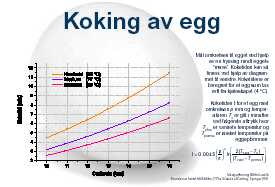

Some years ago I experimented and wrote about what happens if you cook an egg not in boiling water but at, say, 64 °C. I met upon some surprising results ("The opposite boiled egg"), but could not give good reasons for why. But now, at last, the answer to why has appeared in the scientific literature!

According to Harold McGee the "[...] egg white begins to thicken at 63 °C and becomes a tender solid when it reaches 65 degrees". Furthermore, "The yolk proteins begin to thicken at 65 °C and set at 70 °C [...]". (McGee, pp. 85) The molecular gastronomer Hervé This also writes about this in a similar manner in e.g. "Molecular gastronomy - Exploring the Science of Flavor".

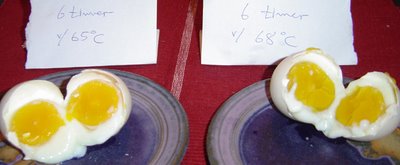

So, for the perfect egg, keep it in a water bath at 65 °C for a long time, and you get an egg with a solid white and soft yolk. I tried cooking times between 1 and 26 hours, and at various temperatures, mostly between 62 and 68 °C.

This is of course inspired by methods used for meat where you can keep the temperature at, say, 58 °C and the meat will stay red still after a day in the water bath (low temperature and sous vide methods). It's not unnatural to think that the same applies to eggs, since both meat and eggs are mostly proteins and water.

The picture to the right shows 68 °C egg creation by Finnish chef Arto Rastas, taken from Anu Hopia's blog molekyyligastronomia. See the bottom for recipe/procedure.

The surprising result

In my experiments the eggs at 62-65 °C turned out "opposite boiled": a solidified (but not entirely solid) yolk came rolling out through a runny white! And on top of it, the time did seem to make a difference. Were my experiments poorly conducted, or was the suggested theory wrong?