Lately, there have been (at least) three interesting podcasts related to science and food:

In Norwegian:

"NRK Verdt å vite spesial" 22. May 2006 - about salt.

Salt is definately a fascinating theme crossing several subjects, both within the sciences and across to other subjects (food, history, social sciences etc.). This programme represents just this interdiciplinary approach.

Erik Fooladi on "Superstreng" no. 34 with Eirik Newth on Kanal 24.

I'm talking about food/kitchen in science education and molecular gastronomy with Eirik Newth on his weekly popular science radio programme. The mp3-file may be downloaded directly from the web site.

In English:

Hervé This in "The Leonard Lopate show" on WNYC New York Public Radio

"Host Leonard Lopate lets you in on the best conversations with writers, actors, ex-presidents, dancers, scientists, comedians, historians, grammarians, curators, filmmakers, and do-it-yourself experts". The French molecular gastronomist Hervé This is co-founder of the research field of molecular gastronomy, no doubt one of the big names in the field. The mp3-file may be downloaded directly from the web site.

Happy listening

Erik

14 Jun 2006

12 May 2006

"Opposite-boiled eggs" - Cooking an egg with soft white and firm yolk

Cooking an egg we usually use boiling water, and we need to monitor the temperature carefully. One minute too much, and we get a less-than-perfect-boiled egg. Reason: the interior of the egg (aka: the proteins in both white and yolk) coagulates/stiffens at far lower temperatures than 100 °C. According to Harold McGee the "[...]egg white begins to thicken at 63 °C and becomes a tender solid when it reaches 65 degrees". Furthermore, "The yolk proteins begin to thicken at 65 °C and set at 70 °C [...]". (McGee, pp 85)

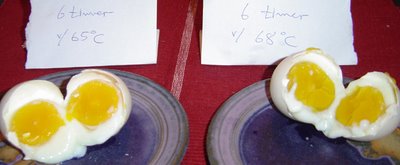

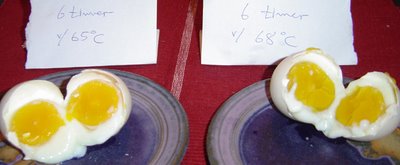

So, my thought was: Since it's the temperature that counts rather than the time, I can keep the temperature at 64-65 °C, and the egg will be perfect (to my taste) no matter how long they are cooked: a fool proof method to eggs with tender solid white and soft yolk! The pictures show eggs cooked ad 65 and 68 °C for 6 and 26.5 hours, respectively.

Hervé This also writes about this: "[...]at 62 °C one of the proteins in the white (ovotransferrin) is cooked, but the yolk remains liquid because the proteins that coagulate first in this part of the egg require a temperature of 68 °C. Obviously this would mean longer cooking times, but the result is a perfectly cooked egg" (This, pp. 31)

The proof is in the pudding, so I tried cooking an egg at 65 °C exactly for an hour or more, and was to put it mildly surprised. The egg came out with a runny white but firm yolk!! These come out the same whether they're kept for half an hour (to ensure the same temperature throughout the egg) or 26°C hours. Another proof, provided the temperature is right, for that the time doesn’t matter in coagulating proteins.

There may be several reasons for this, but one is found in McGee (pp 85): "[…]the major [egg white] protein, ovalbumin, doesn't coagulate until about 80 °C".

So, it seems, this time chemistry played me a trick. We will still have to rely on physics: the reason that we can have eggs with firm white and soft yolk is, when using a temperature well above the coagulation temperature, that the white is "overheated" before the temperature of the yolk passes the point where the yolk stiffens.

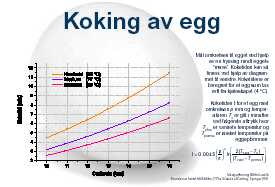

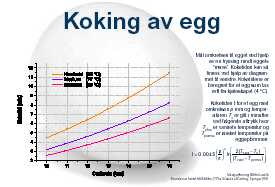

There is, by the way, a mathematic model/equation for this. Have a look at Martin Lersch's web site on Kitchen chemistry for a nice diagram and explanation of this.

Happy cooking

Erik

References and links:

Harold McGee: On Food and Cooking

Hervé This: Molecular gastronomy - Exploring the science of flavor

Martin Lersch's page "Molecular gastronomy and the science of cooking"

Post-comment (feb. 2009):

Douglas Balwin's excellent "A Practical Guide to Sous Vide Cooking" has a section on sous vide cooking eggs

So, my thought was: Since it's the temperature that counts rather than the time, I can keep the temperature at 64-65 °C, and the egg will be perfect (to my taste) no matter how long they are cooked: a fool proof method to eggs with tender solid white and soft yolk! The pictures show eggs cooked ad 65 and 68 °C for 6 and 26.5 hours, respectively.

Hervé This also writes about this: "[...]at 62 °C one of the proteins in the white (ovotransferrin) is cooked, but the yolk remains liquid because the proteins that coagulate first in this part of the egg require a temperature of 68 °C. Obviously this would mean longer cooking times, but the result is a perfectly cooked egg" (This, pp. 31)

The proof is in the pudding, so I tried cooking an egg at 65 °C exactly for an hour or more, and was to put it mildly surprised. The egg came out with a runny white but firm yolk!! These come out the same whether they're kept for half an hour (to ensure the same temperature throughout the egg) or 26

There may be several reasons for this, but one is found in McGee (pp 85): "[…]the major [egg white] protein, ovalbumin, doesn't coagulate until about 80 °C".

So, it seems, this time chemistry played me a trick. We will still have to rely on physics: the reason that we can have eggs with firm white and soft yolk is, when using a temperature well above the coagulation temperature, that the white is "overheated" before the temperature of the yolk passes the point where the yolk stiffens.

There is, by the way, a mathematic model/equation for this. Have a look at Martin Lersch's web site on Kitchen chemistry for a nice diagram and explanation of this.

Happy cooking

Erik

References and links:

Harold McGee: On Food and Cooking

Hervé This: Molecular gastronomy - Exploring the science of flavor

Martin Lersch's page "Molecular gastronomy and the science of cooking"

Post-comment (feb. 2009):

Douglas Balwin's excellent "A Practical Guide to Sous Vide Cooking" has a section on sous vide cooking eggs

23 Mar 2006

New teacher's resource: egg white foam

New teacher's resource (Norwegian only) published on Norwegian Centre for Science in Education pages www.naturfag.no:

Å fange luft med egg - Om trollkrem, skum og proteiner

("Catching Air With Eggs - Concerning Troll's Cream, Foam and Proteins")

How much foam can you get from one egg white? Why is it so difficult to get good whipped egg white foam if a small amount of grease, soap or egg yolk is present? Playing with tasts on troll's cream (troll's cream is a traditional Norwegian dessert made of egg whites whipped with sugar and lingonberries - a light and tasteful foam).

Erik

Inspiration: Pierre Gagnaire and Hervé This (Wind Crystals)

Addition 6. Feb 2007: Gagnaire's pages are now in French only, see Cristaux de vent.

Å fange luft med egg - Om trollkrem, skum og proteiner

("Catching Air With Eggs - Concerning Troll's Cream, Foam and Proteins")

How much foam can you get from one egg white? Why is it so difficult to get good whipped egg white foam if a small amount of grease, soap or egg yolk is present? Playing with tasts on troll's cream (troll's cream is a traditional Norwegian dessert made of egg whites whipped with sugar and lingonberries - a light and tasteful foam).

Erik

Inspiration: Pierre Gagnaire and Hervé This (Wind Crystals)

Addition 6. Feb 2007: Gagnaire's pages are now in French only, see Cristaux de vent.

Addition 2. Jul 2011: Finnish LUMA centre has posted Troll cream on it's experiment pages.

20 Jun 2005

Norwegian school reform: Food in science and science in food

Norwegian education is at the present going through a politically driven reform - new curriculum for all pupils/students, including primary (6-11 yrs), secondary (12-16) and high school (16-18). The current curriculum called L97 (6-16 yrs) is translated into English, but the new ones are not yet translated (not yet finished, but drafts are published). In Norwegian primary/secondary school natural sciences seem to be less focused than in many other countries, and the "food subject" (home economics) has been more or less devoid of scientific aspects - few teachers teach both science and home economics. Is this, maybe, a result of a gender barrier? As home economics traditionally has focused on the "home" part, it has been a women's matter, being placed among the "soft" subjects ("women cook the daily meals at home, restaurant chefs are generally men" as a simplistic angle of incidence).

The new curriculum draft for home economics is interesting in that it focuses more on the food itself than before (which also included house cleaning etc.), and is split into three main subjects:

- Food and lifestyle

- Food and culture

- Food and consumer issues

In spite of the mentioned traditional barriers, there are loads of common subject matters that may very well be taught from an interdisciplinary point of view. Also, many science subjects may be taught with food as a starting point.

I've made a very informal analysis of crossing elements in the curriculum drafts for the two subjects and find that:

- Food in science - 34 out of 129 subjects may be treated with food as a starting point

-Science in home economics - 18 out of 39 subjects may be treated with science as a starting point

Until now home economics has been exempt from examination, but from 2006 this will also be subject to grading. Maybe will this make schools and leaders more committed to treat home economics as a subject on equal terms to other subjects? Will this bing about a change in profile of the subject? Will we see a more theoretical and less practical hands-on home economics? Will the "gender distortion" continue? Will there be a twist towards a more masculine subject (and if so, do we want this to happen)?

Erik

The new curriculum draft for home economics is interesting in that it focuses more on the food itself than before (which also included house cleaning etc.), and is split into three main subjects:

- Food and lifestyle

- Food and culture

- Food and consumer issues

In spite of the mentioned traditional barriers, there are loads of common subject matters that may very well be taught from an interdisciplinary point of view. Also, many science subjects may be taught with food as a starting point.

I've made a very informal analysis of crossing elements in the curriculum drafts for the two subjects and find that:

- Food in science - 34 out of 129 subjects may be treated with food as a starting point

-Science in home economics - 18 out of 39 subjects may be treated with science as a starting point

Until now home economics has been exempt from examination, but from 2006 this will also be subject to grading. Maybe will this make schools and leaders more committed to treat home economics as a subject on equal terms to other subjects? Will this bing about a change in profile of the subject? Will we see a more theoretical and less practical hands-on home economics? Will the "gender distortion" continue? Will there be a twist towards a more masculine subject (and if so, do we want this to happen)?

Erik

8 Jun 2005

Tomato foam

The Norwegian cook, food writer and weekly source and inspiration (at least to me) Andreas Viestad wrote a fascinating piece on tomato mousse:

Run a tomato or three (cut in pieces) in a blender for five minutes. Running for a shorter time will not give the desired result even though it seems finished. Pour into a bowl and leave for a few hours and you get a mousse-like pink jelly. With reference to prof. Hervé This he guesses that the reason may be liberation of pectin from the crushed tomato skin. Pectin is a natural occurring acidic polysaccharide/carbohydrate which contributes to stiffness in some fruit/berry jams and jellies.

I tried this with moderately satisfactory result; a fairly ok foam/mousse on the top with a more soggy mass at the bottom of the glass.

SUGGESTIONS ON WHY THIS DOES WORK (or not work) AND EXPERIMENTS TO TEST THE HYPOTHESES

If pectin is the big point

- using ripe tomatoes should give poorer result that unripe (or less ripe) as the pectin is broken down during ripening. This is by the way the reason why you should use not very ripe berries/fruit when making jam/jelly and more ripe when making juice/syrup. Vice versa: ripe/unripe tomatoes should not make a difference if pectin is not involved.

- Pectin is located in the skin, cell walls and between cells of the tomato. Breaking the cell walls (destroying the cells) by blending should therefore not be a critical point.

If breaking the cells walls is of vital importance

- freezing the tomatoes should be very effective in breaking the cell walls as expansion and formation of sharp crystals by loads of water inside the tomato will cut/explode the cells from within. After freezing, long blending time should not be necessary. Why this should be, I'm not sure. A biologist colleague meant that a possible reason may be that enzymes within the cells are liberated and can react with other parts of the tomato.

Suggested (comparative) experiments:

For consistent experiments, the same blender speed should always be used, and the container should be rinsed between each blending. Washing unnecessary? (most of the tomato is water soluble, but important compounds may be water insoluble)

1) Blending time - cut four tomatoes in two and divide in two heaps (two halves from the same tomato in each group). This way, I'll have to identical heaps. Run one heap for 1-2 minutes, the second for at least 5 minutes. Pour into separate bowls and leave for a few (3-5?) hours.

2) Breaking cell walls - cut four tomatoes in two and divide in two heaps as above. Put each heap in a plastic bag, leave one in the fridge and the other in the freezer overnight. Thaw the frozen tomatoes and run each heap in the blender for an identical period of time. Pour into separate bowls and leave for a few (3-5?) hours.

3) Ripe vs. unripe and blending time double experiment - this is a little less stringent that the point above, but worth a try. You need ripe and unripe (less ripe) tomatoes, ideally from the same plant (grow your own). Make four heaps:

a1) Ripe + short blending time

a2) Ripe + long blending time

b1) Unripe + short blending time

b2) Unripe + long blending time

Run the four heaps separately as for 1). Pour into separate bowls and leave for a few (3-5?) hours.

I'll have to follow up this some time soon (maybe wait for our own tomatoes to ripen?). Results and reflections will be published.

Erik

Run a tomato or three (cut in pieces) in a blender for five minutes. Running for a shorter time will not give the desired result even though it seems finished. Pour into a bowl and leave for a few hours and you get a mousse-like pink jelly. With reference to prof. Hervé This he guesses that the reason may be liberation of pectin from the crushed tomato skin. Pectin is a natural occurring acidic polysaccharide/carbohydrate which contributes to stiffness in some fruit/berry jams and jellies.

I tried this with moderately satisfactory result; a fairly ok foam/mousse on the top with a more soggy mass at the bottom of the glass.

SUGGESTIONS ON WHY THIS DOES WORK (or not work) AND EXPERIMENTS TO TEST THE HYPOTHESES

If pectin is the big point

- using ripe tomatoes should give poorer result that unripe (or less ripe) as the pectin is broken down during ripening. This is by the way the reason why you should use not very ripe berries/fruit when making jam/jelly and more ripe when making juice/syrup. Vice versa: ripe/unripe tomatoes should not make a difference if pectin is not involved.

- Pectin is located in the skin, cell walls and between cells of the tomato. Breaking the cell walls (destroying the cells) by blending should therefore not be a critical point.

If breaking the cells walls is of vital importance

- freezing the tomatoes should be very effective in breaking the cell walls as expansion and formation of sharp crystals by loads of water inside the tomato will cut/explode the cells from within. After freezing, long blending time should not be necessary. Why this should be, I'm not sure. A biologist colleague meant that a possible reason may be that enzymes within the cells are liberated and can react with other parts of the tomato.

Suggested (comparative) experiments:

For consistent experiments, the same blender speed should always be used, and the container should be rinsed between each blending. Washing unnecessary? (most of the tomato is water soluble, but important compounds may be water insoluble)

1) Blending time - cut four tomatoes in two and divide in two heaps (two halves from the same tomato in each group). This way, I'll have to identical heaps. Run one heap for 1-2 minutes, the second for at least 5 minutes. Pour into separate bowls and leave for a few (3-5?) hours.

2) Breaking cell walls - cut four tomatoes in two and divide in two heaps as above. Put each heap in a plastic bag, leave one in the fridge and the other in the freezer overnight. Thaw the frozen tomatoes and run each heap in the blender for an identical period of time. Pour into separate bowls and leave for a few (3-5?) hours.

3) Ripe vs. unripe and blending time double experiment - this is a little less stringent that the point above, but worth a try. You need ripe and unripe (less ripe) tomatoes, ideally from the same plant (grow your own). Make four heaps:

a1) Ripe + short blending time

a2) Ripe + long blending time

b1) Unripe + short blending time

b2) Unripe + long blending time

Run the four heaps separately as for 1). Pour into separate bowls and leave for a few (3-5?) hours.

I'll have to follow up this some time soon (maybe wait for our own tomatoes to ripen?). Results and reflections will be published.

Erik

Addition 11. May 2010: Report from The Flemish Primitives 2010 by Martin "khymos" Lersch has some interesting and possibly relevant info on this matters as well as references. Maybe a solution is to be found therein?

4 Jun 2005

About intersections - music, chemistry and food

In my opinion, some of the most interesting and creative things happen in the intersections between fields of interest. My fate is being both experimental chemist and experimental musician/percussionist, maybe a less-that-obvious combination to look for intersections, but none the more a good reason to construct one. I'm not talking about the more obvious connections between music and chemistry/food/taste/smell (see below), but intersections where chemistry/food/... has a direct impact on the creation or (in my case) performance, of music.

Playing in a improvisation-based jazz trio (just start playing, no songs, arrangements or agreements), I'm constantly looking for things that could trigger new musical ideas. Visual triggers are relatively common (Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, Kari Bremnes and Edvard Munch), but what about scent or taste? What kind of improvised music would result from the scent of rotten eggs, roasted meat, cinnamon etc.? And next: what if the scent was created on-the-go carrying out the chemical reactions while playing? This tastes of futurism, doesn't it? Another idea could be to feed digital data from chemical measurements and analyses into a music computer program using some sort of conversion from chemical data to pitch, rhythm, tempo, dynamics and so forth.

Master chef Pierre Gagnaire has some fascinating thoughts about similarities between music, improvisation and gastronomy, among them:

"[...]I imagine a flavour like a melody, then explore new ground with anxiety but determination to shape an ephemeral jewel from the magical treasures of discovery[...]" - beautiful, and such a striking description of my experiences from freely improvised music as well!

Also, a possibly interesting compilation of scientists/musicians/composers is the New Trier High School Mixing Art/Music and/or Science and Math page

A few more obvious (and thus less interesting?) connections between music and food, molecular gastronomy, chemistry:

- music to accompany food (background music in restaurants). This could be interesting if the music actively comments the food (or vice versa), or even better, if they affect each other.

- musicians/composers that are/were chemists; i.e. A. Borodin)

- chemistry in making instruments; materials, lacquer/varnish etc. (less interesting, maybe, because it's too far a reach for me...)

The search goes on, at a slow pace however, as this is a long term project.

Erik

Playing in a improvisation-based jazz trio (just start playing, no songs, arrangements or agreements), I'm constantly looking for things that could trigger new musical ideas. Visual triggers are relatively common (Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, Kari Bremnes and Edvard Munch), but what about scent or taste? What kind of improvised music would result from the scent of rotten eggs, roasted meat, cinnamon etc.? And next: what if the scent was created on-the-go carrying out the chemical reactions while playing? This tastes of futurism, doesn't it? Another idea could be to feed digital data from chemical measurements and analyses into a music computer program using some sort of conversion from chemical data to pitch, rhythm, tempo, dynamics and so forth.

Master chef Pierre Gagnaire has some fascinating thoughts about similarities between music, improvisation and gastronomy, among them:

"[...]I imagine a flavour like a melody, then explore new ground with anxiety but determination to shape an ephemeral jewel from the magical treasures of discovery[...]" - beautiful, and such a striking description of my experiences from freely improvised music as well!

Also, a possibly interesting compilation of scientists/musicians/composers is the New Trier High School Mixing Art/Music and/or Science and Math page

A few more obvious (and thus less interesting?) connections between music and food, molecular gastronomy, chemistry:

- music to accompany food (background music in restaurants). This could be interesting if the music actively comments the food (or vice versa), or even better, if they affect each other.

- musicians/composers that are/were chemists; i.e. A. Borodin)

- chemistry in making instruments; materials, lacquer/varnish etc. (less interesting, maybe, because it's too far a reach for me...)

The search goes on, at a slow pace however, as this is a long term project.

Erik

1 Jun 2005

Molecular gastronomy/molekylær gastronomi

Molecular gastronomy (Norwegian: molekylær gastronomi). What is this constellation? I believe that the term, as language in general, is in constant development. However, there are a few other words that together could clarify. In my opinion molecular gastronomy contains all the following terms at one time: food, cooking, (natural) science, gastronomy, kitchen chemistry, pleasure, curiosity, and maybe social sciences as well?

One point is that this is not primarily the science of industrial food production, which would be food science, but what happens in the home- or restaurant kitchen from a scientific point of view. How can science contribute to cooking and perception while eating so that cooking develops in new directions (or develops further in an already set direction)? Googling around for the term led me to the wonderful term 'the science of deliciousness’. This link will also lead you to more information and people directly involved in the field.

What fascinates me about this is that it brings together people from different disciplines and different cultures. I'm certain that I as a chemist could contribute to cooking, but I firmly believe that cookery can contribute to my practice as chemist (and not the least, chemistry teacher - more about this at a later point).

Erik

One point is that this is not primarily the science of industrial food production, which would be food science, but what happens in the home- or restaurant kitchen from a scientific point of view. How can science contribute to cooking and perception while eating so that cooking develops in new directions (or develops further in an already set direction)? Googling around for the term led me to the wonderful term 'the science of deliciousness’. This link will also lead you to more information and people directly involved in the field.

What fascinates me about this is that it brings together people from different disciplines and different cultures. I'm certain that I as a chemist could contribute to cooking, but I firmly believe that cookery can contribute to my practice as chemist (and not the least, chemistry teacher - more about this at a later point).

Erik

30 May 2005

Book: The Science of Chocolate

I finished the book "The Science of Chocolate" yesterday night:

In my opinion, the book is ok for people with a certain scientific overview, but a little heavy on the industrial side to be very relevant to everyday molecular gastronomers (see future postings for definition). The experiments part in the last chapter is fascinating, but should have been elaborated further (experiments are described, but the expected outcome is up to the experimenter himself to find out). "Ideal for those studying food science" (from the synopsis) is probably correct, rather than for the science school teacher who wants to play around with food in the classroom (although some of the experiments probably are relevant and usable).

Erik

Post comment march 2009: The book has now come in a second, revised edition.

In my opinion, the book is ok for people with a certain scientific overview, but a little heavy on the industrial side to be very relevant to everyday molecular gastronomers (see future postings for definition). The experiments part in the last chapter is fascinating, but should have been elaborated further (experiments are described, but the expected outcome is up to the experimenter himself to find out). "Ideal for those studying food science" (from the synopsis) is probably correct, rather than for the science school teacher who wants to play around with food in the classroom (although some of the experiments probably are relevant and usable).

Erik

Post comment march 2009: The book has now come in a second, revised edition.

29 May 2005

Start/oppstart

Hensikten med å opprette denne bloggen er at jeg skal kunne poste og reflektere over (natur-)vitenskap, mat, utdanning, musikk og helst det som ligger i skjæringspunktet at minst tre av disse på samme tid. Skal jeg skrive på engelsk eller norsk? Begge deler? Jeg vet ikke. Vi får se

The point of starting this blog is for me to be able to post and ponder on (natural) science, food, education, music and preferable what is a combination of at least three of these at one time. Should I write in Norwegian or English? Both maybe? I don't know. Time will show.

Erik

The point of starting this blog is for me to be able to post and ponder on (natural) science, food, education, music and preferable what is a combination of at least three of these at one time. Should I write in Norwegian or English? Both maybe? I don't know. Time will show.

Erik

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)